Symbols and letters: Chinese literate traditionalism

The Chinese language doesn’t have an alphabet. Unlike its asian contemporaries Japanese and Korean both have alphabets. The linguistic explanation is logographic versus syllabic. The Chinese model is quite ancient while the Japanese and Korean is quite more modern. Yet the syllabic languages use Chinese characters. The uniqueness of the Chinese language is its longstanding un-alphabetic paradigm. Even the Egyptians hailed for their hieroglyphics eventually evolved their system. What is so special about China?

Chinese hanzi is used throughout the asian continent. Both Korea and Japan utilise these characters for their languages. Korea created its own language hangul in the fifteenth century and for Japan hiragana in the fifth century. The use of Chinese characters may suggest the belated effort of a writing system. Writing became relevant for political and technological advancements. Its necessity grew out of urbanisation. For China it began during the Shang dynasty as for Korea it began under the Joseon Dynasty. A sense of nationalism as well as coordination was critical for political logistics. Since the empire needed to keep records of people and taxes. Pictograms which preceded the alphabet was a measure of symbolically recording data. The need to ensure vast quantities of the past whether treaties or philosophies was printed on tablets. Chiseled into the stone from right to left. The larger the group the more necessary the announcement to be encoded.

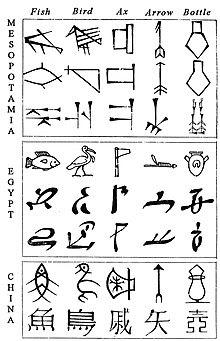

Pictures were the first written symbols. Each of the classic empires had a similar pictographic theory. Each of them began by drawing a fish or a bird. In contrast to other cultures, Egypt’s drawings are more exact; they look like drawing while others look like stick figures. Pictographs developed into logographic signs to expand the language. The evolution of Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Chinese languages slowly morphed their depictions of the figure into a sign. The sign was an ideogram similarly to mathematical symbols such as 1 means one. Just by looking at the number the viewer is aware of its meaning. The same is of the Chinese characters. Fish is pronounced “yu” but the symbol is the convincing part. Chinese has over five thousand characters. Characters that symbolise various features in nature. Instead of drawing a fish or a tree every time, draw a few lines in a certain shape to denote the image itself. Just as the sound bird inflects an image of the creature so does the character. This is not an easy system which is why Chinese is so difficult to learn. A way to ease was to combine symbols in a similar vein that combined pictures would mean a new thing. Chinese already does this with dawn combining two characters.

Japanese kana is a syllabary system in which Chinese characters change from concept to syllable. When seeing a character it will be sounded out instead of applying an image to it. Similar to an alphabet but different. In the alphabet each character makes a sound, individualistically recorded but the syllabary character makes a consonant plus a vowel sound. So in English, two letters are necessary for the sound ka (“k” and “a”) but in Japanese only a single character is necessary. In this way there are less quote on quote letters to be used in a syllabary system. They operate in a similar way as a phrase of letters or symbols will be sounded out. Both grouped characters will sound the same but spelled differently. Japan took on a sound-based system. Even the Egyptians in their hieroglyphics turned into a syllabary system. Hieratic served as the cursive form turning pictograms into loose depictions and then into symbols. The demotic was its successor more easily written with ink on papyrus. It was extended for public use. Simplifying its parental style for others to utilise easily. Coptic was the final nail in the coffin turning the symbolic language into a lettering alphabet. The hellenised influence marked the shift. The addition of autonomous vowels properly distanced itself from its ancient heritage.

The first alphabet goes back to the Phoenicians who inspired the greeks to make their own in the wrong direction. Well even before the Phoenicians, unskilled labourers compiled it because hieroglyphics were too complex. Letters were independent and bunched together to make words which symbolised objects. Yet the sounds mustered by the vowels were not clear and were based on the reader’s inference. In this regard the spoken word was projected on the page and reflected back to the speaker. The word was marked by oral understanding. The difference between the Torah scroll and a Chumash will be blatantly obvious. The scroll has no vowels and the reader must guess but the Chumash presents the vowels to tell the reader how to pronounce the word. Classical arabic, Aramaic and Hebrew were abjads with prior knowledge or context to interpret the word while today they are impure. A great hebrew example would be “zaken” is old and “zakan” which is a beard. Sometimes the sounding is different based on the chronology of the words. In English letters are vowels but that is not the case in the ancient alphabets. Each character has its own sound but that sound is not obvious from the lettering like English. Technically the greeks have the first alphabet given this adage to the current English language.

Alphabetisation is a simplification of the syllabary and even more so of logographs. The letters are to make words that stand for objects. It is twice removed from the object itself. Instead of a symbol whether a picture or an ideogram, it defines the object. Yet to explain a situation various images are necessary to detail the picture. Some are simple other situations are not easy. Ideograms are also not so simple in this regard. A character mixed with other objectification are combined to explain the situation. In an oral society it is more intact. The character phraseology is easy to discern as a reflection of the verbalism but the complexity and advancement of recorded data desires a more advanced system. While this may be a decorative approach, dynasties of eras have survived in China. It may have more to do with expansion and cultural pluralism than primitive simplicity. The birth in the eastern Mediterranean region along the fertile crescent makes sense with a frequent tradespeople who travelled through the region. Spreading their alphabet marked their territory. For an expansion of trade a simpler use of characters to explain enhances literacy. Sharing a literacy with others is a democratising force to discuss with foreigners. A system other cultures could adopt and transfer goods simpler.

An alphabetical system beyond trade was also helpful for the commoners though it not shocking that with the advent of imperial rule of Assyria, Babylon and Persia the use of Aramaic was nationwide. Influenced by the Phoenician alphabet it gradually spread across the kingdom. Diverging into various dialects across different nations. Even if the script was different the sounds were similar. Paleo-Hebrew of the Israelites and Canaanites is identical to the Phoenician alphabet. The current form of Hebrew is a modified form of the Aramaic alphabet (in the Talmud there is a distinction between Hebrew script and Aramaic script). When hellenisation rose Greece sent by their alphabet and when Rome rose they inquired of the Latin alphabet. While not entirely identical the ironic similarities between the Phoenician greek and latin is genuine. The greek alpha and latin a is a right side up Phoenician alep. For bet, the greek and latin added a second loop, for giml greek turned the letter around while latin changed the shape to a curve. Delta is the same as dales though the latin is different but he is backwards for both greek and latin. Though the old italic Etruscan alphabet already made room for the delta to be a d but turning it sideways while lambda was turned forty five degrees east to then be straightened out. Most semitic alphabets varied slightly from the Phoenician with similar sounds while the greeks simply inverted them to write in the opposite direction. Each variation is small and gradual creation of the seaport accounts.

While all the alphabets were swarming, China remained with its logographic creation. Unnerved and unconfined of the shifts. With its centralised isolationist mentality it rarely needed to alter its language. Japan and Korea wishing to distance themselves sought alternatives. By then trade had reached and linguistic information was well expanded. The combination of symbols and letters was a nice touch to combine the western and eastern halves in an eurasian combination. For the Canaanite workers in Egypt hieroglyphics were implausible. They had little relation to the culture and older found it difficult to read. In a sense, the lower class invented the most profound evolution in history. China’s strict hierarchy is unable to reckon with the historical plunges of bottom-up western progression. There is certain ideological input into maintaining the tradition of old. China still uses its old ways because it wasn’t hampered by the outside influences in the same manner. It did have its share of external impacts but linguistically it remained part of its own world. Away from the Middle Eastern crowd that turned into the European centre did not require such noble shifts. China was filled with various dialects but all under the same rubric. Orality was very strong and writing was for the select elites. China remained true to form throughout the generations restricting venturing off into the abyss.

To foreigners the Chinese language is vexing. Head-scratching peculiar signs drawn with precision. The foreigner wouldn’t know where to begin. The characters so foreign how do they sound. Yet the insider recognises the ease of the language. The characters symbolise objects; it makes sense visually. Emphasising meaning at the expense of transparency. Yet its transparency is difficult for foreigners. A young child can point to the character for blue or fire while struggling to sound out the words. To some degree the difficulty of character quantity may have led literacy rates to be minimal until the recent century. Whether this is imperialistic or merely a marker of oral centricity is debatable. Given the extensive strokes to write characters literacy was not necessarily desirable. China did quite well without a writing system. There is an anti-democratic notion in the lapse of literacy but individuality as well as protest is not foreign. There was a strict hierarchy embedded in the social stature which divided the literate from the illiterate. To some extent its isolationism allowed its literacy to remain on the fringes at the same time it was a weapon of the elite to remain atop the food chain. Though its restricted literacy muddled technological advancement, it maintained a communal fire and moral affinity affixed into the core of society.

The pride of china refused the convenience of alphabetising. Yet to some degree it is an inevitable part of their isolating stance. If the alphabet was created by illiterate workers finding a better solution only to be utilised throughout the expansive imperial rule of various cultures. The letters are similar, the sounds are identical. China didn’t have that issue staying true to its successive rule. There is a deep level of respect for keeping the age-old method of literacy. For keeping to their particularistic structure. Adorning the quasi-oral nature of their characters. Keeping the image alive even if it’s expansive and complex. It is cultural and unique to its isolated history.

No comments:

Post a Comment